The follow entry outlines a pre-assessment strategy I would like to use as an EAL teacher team-teaching in a 10th grade biology class. For this lesson, the biology teacher has decided she wants to give her students a better perspective of the impact humans have on planet Earth by having them read an article about the topic.

Here is the article to be read.

My role is to assess the English Language Learners’ readiness for this lesson, differentiate lessons for them, and track their progress. I will do the same for students with special needs as well.

The Pre-Assessment Strategy

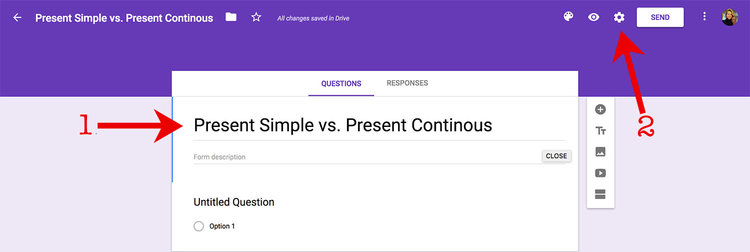

The main concern of the biology teacher is that the ELLs will not have an adequate enough understanding of the article’s vocabulary to fully appreciate it. However, we should not assume that simply because these students do not speak English as a first language that this is the case, so the first step is to administer a quiz to the whole class with ten key vocabulary words from the article in it.

Click here to view the quiz.

As the quiz was taken in a Google Form, I have immediate data which I can now use to divide the class into three levels of academic readiness to eventually read the article.

For this particular activity let us assume that the breakdown is as follows:

Group 1: Five students who got eight to ten correct

Group 2: Twelve students who got five to eight correct

Group 3: Five students who got zero to five correct. Three of these are the ELL students and two have special needs to be addressed

Differentiation and Tracking Progress

Now that we have our pre-assessment data recorded and the class divided into groups based on their readiness to read the article, I can focus my attention on the ELLs and those with special needs. However, as I am teaching very closely with the biology teacher so as to not alienate the ELLs, we both will have a responsibility and role in differentiating instruction so that everyone gets the most out of the article to be read.

For group 1 who already has a fairly strong knowledge of the vocabulary, I will assign them to a work station with the intent of expanding their knowledge rather than reiterating what they already know. To accomplish this I will provide them with a list of ten synonyms for the vocabulary they already ready know and ask them to attempt to match them with the originals by searching on the web with iPads. Finally, to assess their progress I will ask each student to come up to my desk and give me the synonyms.

Group 2 represents the majority of the class with average knowledge of the necessary vocabulary who ideally need to be at group 1 capability before reading the article. To achieve this I believe these students need to use the vocabulary in contextual situations so I will have them write sentences. First these twelve students will be provided with the definitions of the sentences and then they will be tasked with writing a single sentence to demonstrate understanding. To track their progress I will walk around their desks and ask them to read some sentences to me. If they are accurate I can consider this exercise to be successful in preparing them for the article.

Finally group 3, which consists of ELLs and those with special needs, are the group which I consider to need instruction in the vocabulary from scratch and not simply extra support like the others. For the ELLs, I do not see the value in explaining the meanings of the terms to them and it will be much more effective if they learn through self-discovery. Therefore, I will task them with finding the meanings in their first languages with iPads. After they have done this I will ask them to retake the original quiz and compare their scores. If they have significantly improved, and if time allows, I will assign them the same task as group 2 students, then assess their progress by reading their sentences.

With regard to the two students with special needs (e.g., dyslexia and ADHD) in group 3, I do not believe separating or pulling them from the classroom is necessary, so I will ask the special education teacher to join this lesson and work with them. The linguistic task I will assign to them is to find examples of the vocabulary with iPads. For example, they will search for images of the term ‘destruction’ and present it to me as proof of understanding. If the student is able to, I will ask them to give me a verbal example of term in a sentence to demonstrate understanding. Finally, I will ask them to take the original quiz again to measure learning.

Conclusion

The benefit of the pre-assessment is that I as a teacher can see where my students are at before throwing them into a complex task. When differentiating instruction I believe the goal should be to bring the whole class to the same point, but different paths will have to be taken. For those with a strong understanding already, they will be challenged most by expanding their knowledge. For the middle zone, these students will need reinforcement by means of contextualized tasks, such as writing sentences. And for the student who need more assistance, the key is to not alienate and pull them out of the classroom, but to utilize their strengths (e.g., first languages, research skills) so that they can be on par with the rest of the class by the time we begin the main lesson.

Here is a flowchart outlining the thought process for reference: